Cast away on a desert island, surviving on what nature alone can provide, praying for rescue but fearing the sight of a boat on the horizon. These are the imaginative creations of Daniel Defoe in his famous novel Robinson Crusoe. Yet the story is believed to be based on the real-life experience of sailor Alexander Selkirk, marooned in 1704 on a small tropical island in the Pacific for more than four years, and now archaeological evidence has been found to support contemporary records of his existence on the island.

Alexander Selkirk was born in the small seaside town of Lower Largo, Fife, Scotland in 1676. A younger son of a shoemaker, he was drawn to a life at sea from an early age. In 1704, during a privateering voyage on the Cinque Ports, Selkirk fell out with the commander over the boat's seaworthiness and he decided to remain behind on island, now named Robinson Crusoe, where they had landed to overhaul the worm-infested vessel.

He cannot have known that it would be five years before he was picked up by an English ship visiting the island.

Selkirk first went to sea at fifteen to escape a formal charge of “undecent beaiviar.” Later, as a grown man, he joined the crew of the Cinque Ports, a one hundred thirty ton vessel of billowing sails and swelling planks. Selkirk was the master navigator as they traveled south along the coast of Brazil.

After reaching the southern tip of Argentina they turned north following the coast of Chile. However, diminishing rations and disease saw their original crew of ninety wither to forty-two. The ship was strained against a relentless ocean. The situation worsened when an infestation of worms reduced portions of the hull to a near pulp, yet relief lay ahead.

In September of 1704, the tiny island of Juan Fernandez appeared on the horizon. Captain Stradling ordered the crew to anchor in the island’s bay, providing the men with a needed respite from their frustration and suffering.

The sojourn on the island was brief; the captain was anxious to return to his ship and his voyage. Selkirk insisted, however, that the ship was no longer seaworthy, and that the leaking hull would succumb to the temperament of the ocean or enemies. He urged captain and crew to remain on the island and wait for help, but they ignored him. Selkirk’s defiance grew, until finally Stradling ordered that Selkirk be left on the island with only his sea chest, bedding, and clothing. Moments later the ship and the crew set sail while Selkirk watched in anguish from the lonely shore of the island. He shouted for them to return, begging for forgiveness– but the ship continued. Among his possessions was a pistol, gunpowder, bullets, a knife, a hatchet, navigation instruments, a bible, a flask of rum, and enough food for just a few days.

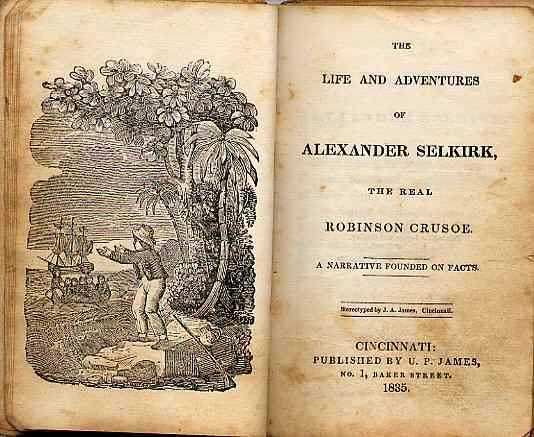

|

| Romanticized portrait of Selkirk as Robinson Crusoe |

For the first few days of his self-imposed marooning, Selkirk explored the area around the beach. Goats, cats, and rats, escapees from Spanish ships, populated the small island. Fresh water pools and springs were plentiful and the climate pleasantly temperate. It was truly an island paradise, but Selkirk watched the horizon line, praying to see a sail. After days of no rescue, he began to make preparations for a longer stay. He built a hut from pimento trees and covered it with long grasses. He lined the interior with goatskins. The weeks stretched out and Selkirk, melancholy sometimes to the point of near suicide, kept a fire burning on a nearby hill hoping to lure in an English ship. Upon his exploration of the island’s sharp lava rocks and lush vegetation he found fresh water to drink, seals to provide meat, and indigenous plums to protect against scurvy.

Selkirk’s warnings of an unsafe ship proved accurate– within a month of his exile, the Cinque Ports gave in to its fate and sank off the coast of Peru. Many of the men drowned, and those remaining, including the captain, made it to the shore of an island where fourteen more died.

Months passed. Years began to pass. It was a late afternoon in 1709 when a ship approached the island. Though he could not determine the nationality of these men, he was desperate and ran to the shore. Quickly, he ran across the beach signaling them with a burning branch. The men disembarked onto the island, guns drawn and aimed at the weathered face of Selkirk. With his hands above his head, he told them he was marooned. The crew offered him room aboard the ship. Selkirk would only join if he was assured Stradling, his former captain, was not present. The name was of no meaning to these men searching only for food and fresh water.

Captain Woodes Rogers later wrote of Selkirk’s marooned existence in his book A Cruising Voyage ‘Round the World:

When his clothes were worn out he made himself a coat and a cap of goat skins, which he stitched together with little thongs of the same, that he cut with his knife. He had no other needle but a nail; and when his knife was worn to the back he made others, as well as he could, of some iron hoops that were left ashore, which he beat thin and ground upon stones. Having some linen cloth by him, he sewed him some shirts with a nail and, stitched them with the worsted of his old stockings, which he pulled out on purpose. He had his last shirt on when we found him on the island.

After four years and four months he was returning home. Several people who spoke to Selkirk after his rescue (such as Captain Rogers and the journalist Steele) were impressed by the tranquillity of mind and vigour of the body that Selkirk had attained while on the island. After his rescue, a different isolation set in. Selkirk returned to his hometown of Largo, where he was unable to acclimate to the regimen of daily life. He returned to Scotland a rich man from the capture of the Spanish ship, but he made his home in a cave where he lived a reclusive life for the next fifteen years. He married in 1717, but soon, at the age of forty-five, he returned to sea.

Alexander Selkirk died at 8 p.m. on 13 December 1721 while serving as a lieutant on board the Royal ship Weymouth. He probably succumbed to the yellow fever which had devastated the voyage. He was buried at sea off the west coast of Africa.

Around 2000, an expedition led by the Japanese Daisuke Takahashi, searching for Selkirk's camp on the island, found part of an early eighteenth (or late seventeenth) century nautical instrument that almost certainly belonged to Selkirk.

|

| Powder horn that belonged to Selkirk |

No comments:

Post a Comment